100 years

Can business change?

Corporations have no trouble building new products or entering new markets. Yet improving diversity remains an enduring challenge.

Doctor Ivy Williams had to wait a long time before becoming the first woman to be called to the English Bar in 1922. The 45-year -old completed her exams in 1903 but was prevented from receiving her qualifications until Oxford University allowed women to matriculate in 1920. What cleared her path was the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, which enabled her to join Inner Temple as a student. Williams described her elevation as ‘the dream of my life’, even though she eventually chose teaching over a career as an advocate.

Helena Normanton would become England’s first practising female barrister just a few months later, going on to be the first female counsel in cases in the High Court of Justice, the first woman to secure a divorce for a client, the first to lead the prosecution in a murder case – and the first to conduct a trial in America.

Today, a century on from the passage of Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, attitudes to diversity across business and society have changed for the better. But what success has been achieved has quite rightly bred the desire for further progress in all forms of diversity – and at all levels of the corporate world.

Some of the involuntary flag carriers for change are frustrated that more has not been achieved in recent years. Dame Marjorie Scardino became the first female chief executive of a FTSE 100 company in 1997, but when she stepped down from education group Pearson 15 years later she lamented that more women hadn’t had similar careers.

‘I have always in life thought that we ought to be able to be chosen to do things on our own merits rather than something we can't help,’ she said. ‘I don't think women are necessarily as different from men as all of these reports say.’

More recently, even the most successful business leaders fear that progress is not built on solid foundations. Dame Inga Beale, the former boss of insurance market Lloyd’s, is quoted in the latest update from the Hampton-Alexander Review – a body which tracks the progress of UK companies in appointing women to board seats – as saying:

‘Those women who have been a CEO in a large organisation will say, and in fact some will know, that our successors are going to be men. Speaking to several of them, the common view is that chairs think they have done their bit by hiring a woman, now the role can go back to a man. It feels as though we took two steps forward and are now taking one step back.’

Likewise the legal profession still has a long way to go. In 2017 the UK regulator, the Solicitors Regulation Authority, found that women accounted for 48 per cent of all lawyers in private practice in England and Wales but just 33 per cent of partners. Some 21 per cent of private practitioners are from black, Asian and mixed-ethnicity (BAME) backgrounds, but in the largest firms that proportion was just 8 per cent.

Accelerating the pace of change comes from creating more welcoming working conditions, encouraging talent through mentoring the next generation and setting ambitious targets – while remembering to celebrate progress.

In February, Congress applauded when President Trump pointed out in his State of the Union address that out that there were more women in the US workforce than ever before – and a record number of female legislators. That journey has been mirrored in the UK, where the percentage of women MPs has risen from 18 per cent in 1997 to 32 per cent today, in part thanks to the introduction of more family-friendly voting times. However this is still a long way short of the global trailblazer, Rwanda, whose parliament is more than 60 per cent female.

Indirect measures such as these can help to build more diverse organisations across all parts of society. But there are also many who believe that quotas are the only way to achieve true balance. In 2014, Lloyds Banking Group pledged to add close to 1,000 women to its 8,000-strong managerial ranks by 2020, ensuring a woman was put forward for every senior role that came up.

‘It is very important that everything should be meritocratic and based on performance,’ Lloyds boss Antonio Horta-Osório said at the time. ‘I am absolutely sure all the women we are hiring and promoting would not like it any other way.’ Last year, the bank added a new target: for 8pc of its top tier to be drawn from BAME communities by 2020.

It is encouraging that the diversity debate has opened out. Many large organisations have recognised the benefits of recruiting from a broader set of universities. Working practices are evolving to make business more accessible, and gender pay gaps are in the headlines. The challenge for business is to do more than just shine a light on the problems, but to make real strides towards solving them.

There is a demonstrable financial imperative to getting it right. A 2017 McKinsey study of more than 1,000 companies in 12 countries found that those whose executive teams ranked in the top quartile for gender diversity were 21 per cent more likely than those in the bottom to achieve above-average profitability. And the businesses with the most ethnically diverse top teams were 33 per cent more likely to outperform those with the least.

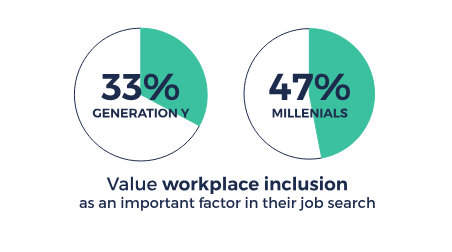

Then there is the pressure from below. According to research from the American Institute for Public Relations, 47 per cent of millennials (classed as those born between 1981 and the mid-1990s) considered workplace inclusion an important factor in their job search, compared to 33 per cent of those in the previous generation. In the global race for talent, the most diverse organisations are more likely to win.